Revisiting Crawford v. Washington

, Revisiting Crawford v. Washington, in Nunn on Evidence (October 21, 2025). | Permalink

On March 24, 2025, the Supreme Court issued a routine denial of certiorari in Franklin v. New York. Tucked inside the order, however, were two statements that signaled potential trouble for the most significant Confrontation Clause decision of the last few decades, Crawford v. Washington.

In a direct critique, Justice Alito called for the Court to reconsider Crawford, arguing two pillars supporting the decision have crumbled with time. First, he contended that Crawford’s historical account, which claimed to capture the original meaning of the Confrontation Clause, is now challenged by more recent scholarship that casts doubt on its core premises. Second, and perhaps more pointedly, he argued that Crawford’s promise to replace an unpredictable legal test with a clear, workable one has failed spectacularly. Far from providing clarity, post-Crawford doctrine has produced a jurisprudence that, in his words, “continues to confound courts, attorneys, and commentators,” driving the point home with a string of citations describing the doctrine as everything from a “morass” and “incoherent” to “unstable,” “unnecessarily complex,” “unworkable,” and a “mess.”

In a separate opinion, Justice Gorsuch likewise questioned the current path. He criticized reliance on the judge‑made “primary‑purpose” test as a necessary condition for relief, noting that the approach “came about accidentally” and that the Court has never truly tried to justify it based on the Sixth Amendment’s original meaning. And, echoing his concurrence last term in Smith v. Arizona, he cautioned that the primary‑purpose framework may be a “limitation of our own creation” on the confrontation right.

The question thus looms. If the Court takes up Justices Alito’s and Gorsuch’s invitation, will it overrule Crawford?

This post examines history, doctrine, and the nine individual Justices who now make up the Court to offer a prediction. Notably, my analysis today is descriptive, an attempt to map the votes and predict what the Court will do, not a normative account of what I think it should do. I’ll save my normative thoughts for a later date (this post is long enough already!).

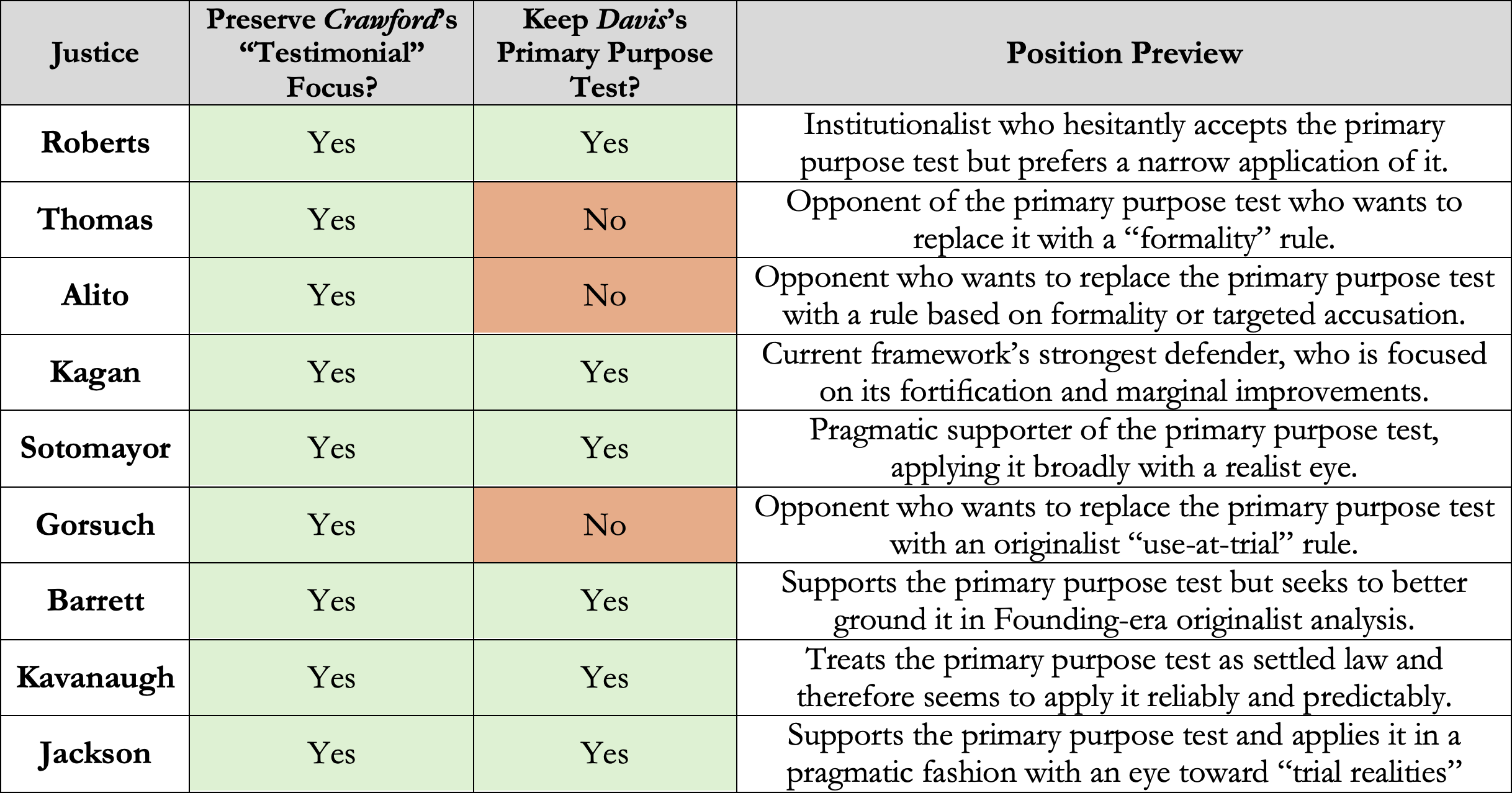

To ground my prediction, my post will first provide a brief overview of current Confrontation Clause jurisprudence, starting with Crawford and working through its extensive progeny. With that foundation, I’ll survey the posture of each justice. This requires disaggregating the capacious notion of “overruling Crawford” into three distinct doctrinal issues. The first, and most foundational, is whether there is any real appetite on the Court to repudiate Crawford’s core and return to the Ohio v. Roberts era, where the Confrontation Clause was seen as a flexible tool for ensuring reliability rather than a procedural guarantee of cross‑examination. The second issue, which is the central battleground, is the extent of support for the current framework of determining whether statements are “testimonial,” and therefore within the ambit of the Sixth Amendment, by using the “primary purpose” test advanced in Davis v. Washington and Michigan v. Bryant. Finally, the third issue involves the alternatives to current doctrine. For the justices who want to define “testimonial” in a materially different way, what models do they propose, and are these competing theories reconcilable?

Ultimately, my analysis suggests that Crawford’s central move of repudiating reliability principles within the Confrontation Clause is perfectly safe. The real drama is over Davis’s and Bryant’s primary‑purpose test. At least three justices would jettison this doctrinal mainstay entirely. Nevertheless, despite those sharp critiques, the primary‑purpose test is likely to survive not because it enjoys universal support, but because its most vocal critics are deeply and irreconcilably divided on what should take its place.

I. Modern Confrontation Clause Doctrine

The Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause gives a person accused of a crime the right “to be confronted with the witnesses against him.” This right has deep historical roots, born from a reaction to a practice in English trials widely seen as illegitimate and unjust. In the famous 1603 treason trial of Sir Walter Raleigh, for example, the prosecution relied on a written accusation from his alleged accomplice, Lord Cobham, who never appeared in court. Raleigh passionately argued for his right to have Cobham brought before him, famously stating, “Let my accuser come face to face, and be deposed.” The judges refused this request, and Raleigh was convicted based on that untested paper evidence. This practice of “trial by affidavit,” where a person could be condemned by a witness they never got to question, became the textbook example of the abuse the Confrontation Clause was designed to prevent.

In its landmark 2004 decision, Crawford v. Washington, the Supreme Court held that deep historical lineage underlying the Confrontation Clause shows that it was enshrined within the Sixth Amendment to prevent this kind of “trial by paper.” Specifically, the Court ruled that the Confrontation Clause prohibits the use of “testimonial” statements, or statements made with the expectation that they will be used in a criminal investigation or prosecution, as a substitute for live testimony.

Notably, Crawford was a major shift. For the first time, the Crawford Court reconceived the Clause as guaranteeing a procedure, cross‑examination for testimonial statements, rather than just a judicial assessment of “reliability.” In other words, under Crawford, a defendant always gets to challenge their accuser in person, even if a judge decides that an out‑of‑court testimonial statement is trustworthy and cross‑examination is likely to be rather ineffectual.

To appreciate the importance of Crawford, consider its predecessor Ohio v. Roberts. Roberts did not see a defendant’s right to cross‑examine accusers as inviolable, but instead allowed judges to admit hearsay if it bore “adequate indicia of reliability” because it fit a firmly rooted exception or otherwise looked trustworthy on the facts. Crawford replaced Roberts with a distinct sequence. If the prosecution offers a testimonial statement for its truth, the defendant must have had a prior opportunity to cross‑examine the declarant. That shift put the Clause’s focus on adversarial testing rather than judicial assurance.

Crawford thus held that the right to confrontation applies to all out‑of‑court statements that are “testimonial.” But that clarification immediately spawned another question. What does it mean for a statement to be testimonial? Somewhat curiously, the Crawford court itself did not try to write a full definition of “testimonial,” beyond noting that a formal, recorded station‑house interrogation clearly qualified. And that omission left a critical gap. Lower courts immediately struggled with this ambiguity, especially in cases involving informal statements made to police during chaotic 911 calls or at active crime scenes. In the years following Crawford, it therefore became clear that the Court would need to provide a standard for pinpointing which statements fell within classification as “testimonial,” giving rise to the right to Confrontation, and which fell outside that label and beyond the reach of the Sixth Amendment.

The Court’s first answer came in Davis v. Washington, decided with Hammon v. Indiana. These cases introduced an objective “primary purpose” test to determine if a hearsay statement was indeed testimonial and correspondingly implicates the Confrontation Clause. In Davis, a 911 call made during a domestic dispute was held nontestimonial because the caller was speaking about events as they were happening to enable police to resolve a present emergency. In Hammon, by contrast, statements to police at the scene after the dispute had ended were held testimonial. The emergency was over, and the officers were separating the parties to investigate “what happened” for a potential future prosecution. Together, these cases established the primary‑purpose test for determining if a statement is testimonial and, in applying that test, identified a core distinction in its operation: statements are nontestimonial when their primary purpose is to resolve an ongoing emergency, but testimonial when their primary purpose is to establish or prove past events potentially relevant to later criminal prosecution.

Five years later, the Court applied and elaborated upon the primary‑purpose test in Michigan v. Bryant. There, a mortally wounded victim’s statements at a gas station were held nontestimonial because, viewed objectively and in context, reasonable participants would have understood the exchange as aimed at addressing an ongoing emergency rather than creating evidence for trial. Bryant thus confirmed that the primary‑purpose inquiry is functional and context dependent, evaluating the statements, actions, and surrounding circumstances of the encounter.

The Court continued this contextual approach in Ohio v. Clark, which adapted the primary‑purpose test to non‑police settings. There, a preschooler’s statements to his teachers identifying an abuser were held nontestimonial. The Court, in an opinion by Justice Alito, found the “primary purpose” of the conversation was to protect the child from an immediate threat, not to build a criminal case. It held that even though the teachers were mandatory reporters, they were not acting as law enforcement surrogates during the informal conversation, which was focused on the child’s safety. Clark thus again confirmed the primary‑purpose inquiry is a flexible tool that adapts to different contexts, rather than a rigid rule about police conduct.

A different line of cases addressed forensic proof. In Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, the Court held that sworn lab certificates reporting drug analysis results can be testimonial, reasoning they are created for an evidentiary purpose. Moreover, in Bullcoming v. New Mexico, the Court rejected “surrogate testimony” by a colleague who neither performed nor observed the test at issue. These cases, often decided over strenuous dissents arguing that neutral lab reports are not conventional “witnesses,” collectively insisted that when the primary purpose of a lab test is to establish a fact for trial, and the state relies on an analyst’s assertion to prove a fact, the analyst is a witness whom the defendant has the right to confront. Importantly, the primary‑purpose test distinguishes between different types of records. Records created for routine administrative or business purposes generally fall outside the Clause. But as the Court underscored in Melendez-Diaz, records whose primary purpose is use in a prosecution, such as a certified lab report, are considered testimonial. Together, these principles keep the focus on whether the government is substituting a person’s testimonial assertion for live testimony at trial.

In more recent years, a fractured decision in Williams v. Illinois briefly muddied the waters. There, a testifying expert referred to a DNA profile created by a non‑testifying analyst. A plurality, led by Justice Alito, treated the expert’s reliance on the outside lab’s profile as not offered for its truth, but rather as part of the “basis” for the expert’s own opinion under evidence rules like Rule 703. Justice Thomas concurred in the judgment only, advancing a different rationale that turned on formality. Given the absence of a majority opinion, lower courts split on how to read Williams, with many prosecutors using the plurality’s “basis testimony” logic to introduce accusatory forensic facts without confronting the analyst who created them. The Court has since cleaned up much of that confusion. In Hemphill v. New York, an 8‑1 Court rejected a “door opening” escape hatch that allowed judges to admit testimonial hearsay to correct supposed misleading impressions at trial. And in 2024, Smith v. Arizona directly addressed the Williams problem. Smith held that when an expert relays an absent analyst’s factual statements and those statements matter only if true, the jury has received them for their truth, so the Confrontation Clause applies in full. As Justice Kagan wrote for the Court, echoing a dissent from Williams, this move prevents the state from using evidence rules as an “end run” around the Constitution. Those decisions reinforce Crawford’s core, and they replace workarounds with straightforward, administrable rules.

One final point completes the modern doctrinal map. Like many constitutional rules, Crawford’s demand for cross‑examination is not absolute. It works alongside a few historically recognized exceptions that apply when a witness is unavailable to testify.

The first is for “former testimony.” If a witness is now unavailable, their testimony from a previous hearing can be admitted, but only if the defendant already had a full and fair opportunity to cross‑examine them during that earlier proceeding. This isn’t so much a true exception to Crawford’s logic as it is a fulfillment of it, just at an earlier time.

Second, the Crawford Court itself acknowledged the unique, historically‑grounded exception for “dying declarations.” The Court admitted that this exception for statements made by someone who believes they are about to die is an anomaly, or sui generis. It doesn’t fit neatly into the cross‑examination framework, but the Court accepted it based on its deep roots in the common law, treating it as a one‑of‑a‑kind exception that survived the constitutional shift.

Finally, a defendant forfeits their confrontation right through “forfeiture by wrongdoing.” This rule prevents a defendant from benefiting from their own wrongful act of making a witness unavailable. In Giles v. California, however, the Court added a crucial limitation by holding that, for this exception to apply, the prosecution must prove the defendant acted with the specific intent to prevent the witness from testifying. It’s not enough to show that the defendant’s actions simply resulted in the witness’s absence. For example, in a domestic abuse case, if the defendant murders the key witness against him, the victim’s prior testimonial statements are only admissible under this rule if the prosecution can show he committed the murder for the very purpose of silencing her. If the assailant committed the crime because of a fallout from an affair, conversely, the exception does not apply because the motive was not to prevent future testimony.

Stepping back, after two decades, the modern doctrine has a stable architecture, even if it has persistent fault lines. The core rule is clear. Crawford’s procedural right to cross‑examination “testimonial” statements has definitively replaced Ohio v. Roberts’s judicial reliability screen. And the subsequent cases, Crawford’s progeny, have built out this framework. The Davis and Bryant line gives lower courts the primary‑purpose test to sort statements into “testimonial” accusations or “nontestimonial” cries for help. Meanwhile, the forensic cases, from Melendez-Diaz to Smith, have insisted that lab reports and analyst statements created for prosecution are testimonial, and they have systematically shut down evidentiary “end‑runs” like calling an analyst’s findings “basis testimony” or “door opening.” Finally, the doctrine recognizes a few narrow, historical exceptions, like dying declarations and forfeiture by wrongdoing, that operate as safety valves.

But this brings us to the key fault line, the one signaled by Justice Alito in Franklin v. New York. The entire structure, from Davis to Clark to the forensic cases, hinges on one central question: Is a statement “testimonial”? And that question, for now, is answered by the “primary purpose” test. This test requires judges to evaluate the circumstances and objectively determine the main reason for the statement. Was the primary reason for the exchange to get help in an emergency, or was it to create a record for a future trial?

This very tool, the primary‑purpose test, is what’s now under fire. Justice Alito and Justice Gorsuch have openly questioned its utility and historical basis. Justice Thomas has long offered a competing rule based on “formality” rather than “purpose.” And these disagreements are not just academic tinkering. They go to the heart of the Crawford project and raise the central question we must now explore: Is the primary‑purpose test the best, or even the correct, way to determine if the Confrontation Clause applies? Or, as its critics argue, is it an “ahistorical gloss” that has created its own “morass” of confusion? The caselaw we’ve just covered is the terrain for this debate. The next section takes this foundation and considers the more exciting question. What would the current Court do if asked to keep, modify, or overrule Crawford’s framework today?

II. The Justices’ Views

With a background in Confrontation Clause jurisprudence behind us, we now turn to the pressing issue. If a clean vehicle arrived tomorrow, how would the current Court vote on whether to affirm, modify, or overrule Crawford v. Washington?

Notably, some initial clarifications are in order. Crawford itself was a broad decision with multiple holdings, meaning that we need to be careful about what exactly the justices might want to affirm or repudiate in a future opinion. To “repudiate Crawford,” for instance, could mean two very different things. On the one hand, it could imply that a Justice wants to restore Ohio v. Roberts’ judge‑centered reliability screen as a functional bypass to the Confrontation Clause. On the other hand, a Justice might agree that the Roberts era of reliability‑centered confrontation jurisprudence was indeed erroneous, but also find error in the alternative jurisprudential path that began with Crawford’s testimonial framework and that has since been operationalized through the “primary‑purpose” line of cases which followed.

Fortunately, the current Court seems to have unanimity on the first point, making our task much easier. My sense is that, despite the calls for reconsideration of Crawford, there is no real constituency for resurrecting Roberts. The Court has repeatedly described that regime as unpredictable and atextual, and the recent cases do not read like a Court that wants to hand trial judges a discretionary license to admit hearsay because it seems trustworthy. The point is clearest in the Court’s recent decision in Hemphill v. New York, which as we saw, rejected a “door‑opening” theory that allowed trial judges to admit testimonial hearsay on the basis that the defense had created a misleading impression. That opinion treated confrontation as a method, not as a reliability screen in new clothes, and it carried eight votes.

The same baseline appears in the writings of those Justices most skeptical of Crawford’s downstream doctrine. Justice Thomas has said outright that the Roberts test was “inherently, and therefore permanently, unpredictable.” Justice Alito’s previously mentioned statement in Franklin v. New York called for reconsidering Crawford’s premises, but even there he did not suggest reviving judicial reliability balancing. His debate is about the meaning of “witnesses” and the scope of the Clause, not about returning to Roberts and the invocation of reliability within Confrontation Clause jurisprudence.

Ohio v. Roberts is thus well and truly dead, meaning that the real fault line arises from that second question: the viability of the primary‑purpose test. Should the Court keep Crawford’s testimonial framework and the primary‑purpose test it engendered? Or, as its critics argue, should that test be jettisoned in favor of a different way to define “testimonial,” like formality or targeted accusation? What follows is a survey that asks this central question of every Justice.

Chief Justice Roberts

Chief Justice Roberts is a careful institutionalist, and his approach to the Confrontation Clause reads that way. My sense is that he is not looking to jettison Crawford’s testimonial framework, nor is he seeking to replace the primary‑purpose test it gave rise to. Instead, Chief Justice Roberts seems committed to a managerial project. He accepts Crawford’s core rejection of Roberts, and his forward‑looking focus seems to be on trimming the doctrine’s rough edges rather than fundamentally remaking it.

Consider his jurisprudential track record. Most notably, Roberts has consistently embraced the primary‑purpose test, joining the majority opinions in both Davis v. Washington and Michigan v. Bryant. Returning to Bryant, for instance, he joined Justice Sotomayor’s opinion holding that a mortally wounded victim’s statements to officers at a chaotic scene were non‑testimonial. The Court found that a reasonable participant would understand the exchange as directed to an ongoing emergency, not to creating trial evidence. In many ways, Bryant is a functionalist application of Crawford that keeps pleas for help and other exchanges intended to stabilize a scene on the non‑testimonial side of the line. My sense is that the Chief sees Davis’s and Bryant’s primary‑purpose test as a sensible way to keep the Clause from swallowing ordinary police response.

A similar pragmatism seems to drive his views on experts and laboratory work. Ever since joining the Court, Roberts has been uneasy with treating every lab document as the constitutional equivalent of an accusing witness. He joined the dissent in Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, which, as noted earlier, argued that routine analyst certificates are not the sort of accusatory testimony that worried the Framers. He likewise joined the dissent in Bullcoming v. New Mexico, which would have allowed the “surrogate testimony” that the Court rejected. But those votes were not pleas to reintroduce reliability balancing, nor were they even a repudiation of Crawford. Rather, they seemed to simply reflect a narrower view of who counts as a “witness against” the accused in the forensic context and a preference for letting evidence law shoulder more of the load where appropriate.

The Chief’s alignment in the modern expert cases makes this concrete. Returning to Smith v. Arizona, the recent case we discussed concerning expert testimony, the Court held that when a testifying expert conveys the factual assertions of an absent analyst, and those assertions matter only if true, the statements have been received for their truth and the Confrontation Clause applies. The Chief did not resist that bottom line given the case’s posture. He did, however, join Justice Alito’s concurrence. That opinion urged courts to retain the ability to admit some expert basis material with a limiting instruction that it is not received for its truth. This approach relies on Federal Rule of Evidence 703 and trial management rather than constitutionalizing the entire field of expert testimony. His parallel vote in Samia v. United States, where he joined an opinion presuming jurors can follow limiting instructions in the context of redacted co‑defendant confessions, reinforces this pattern. The Chief is skeptical of constitutionalizing what he sees as ordinary evidentiary management, preferring instead to trust traditional trial tools like limiting instructions to keep evidence in its proper lane. Read together, his consistent view becomes clear. He accepts Crawford’s core, but he would balance it with confidence in traditional trial evidentiary tools to keep the application of the primary‑purpose test narrow.

What does that mean going forward? My sense is that the Chief would keep the testimonial framework and the primary‑purpose test, but he would prefer to apply both narrowly with an eye to administrability. He is unlikely to join Justice Thomas’s effort to replace the primary‑purpose test with a formality and solemnity rule. He also isn’t apt to follow Justice Alito into an overhaul that would confine the Clause to formal statements or targeted accusations alone. Rather, he seems committed to a managerial project within the existing architecture. He would keep the primary‑purpose test, trim its rough edges, and leave Crawford’s core rejection of Roberts untouched.

Justice Thomas

To my mind, Justice Thomas is the most straightforward case. He is the only current justice who was in the Crawford majority, and he remains committed to its rejection of the Ohio v. Roberts reliability regime. But he would absolutely jettison the doctrinal framework that Crawford subsequently created. For Justice Thomas, the Court’s entire primary‑purpose line of cases is a mistake. He would therefore discard that functional, motive‑based test and replace it entirely with a singular, formalist rule.

The Confrontation Clause, in Justice Thomas’s view, applies only to out‑of‑court statements that carry a specific degree of formality and solemnity, making them the functional equivalent of in‑court testimony. Pursuant to his reading of the Confrontation Clause, the Framers enshrined the confrontation right in response to a specific abuse, trial by affidavit, epitomized by the Case of Sir Walter Raleigh. The Sixth Amendment’s “witnesses” were thus those who bore testimony in a solemn, official way, the sort of thing that mimics what happens in court. Think sworn affidavits, depositions, or structured interrogations that carry the same formal weight. For Justice Thomas, however, the Clause does not cover every out‑of‑court remark. It addresses only those statements that, by their form and context, are the functional equivalent of in‑court testimony.

Thomas has already championed this view numerous times, arguing against the primary‑purpose framework that has arisen from the Crawford line of cases. In his separate writing in Davis, for instance, he criticized the primary‑purpose test on two grounds. First, it sweeps in statements that do not carry the formal attributes that history associates with testimony. Second, it tasks judges with divining mixed motives, which he sees as unworkable in practice. His objections reappear in Michigan v. Bryant, where, as mentioned before, he concurred in the judgment while refusing to apply the primary‑purpose test. He concluded the statements there were non‑testimonial because the police questioning was not a formalized dialogue and produced no formalized testimonial materials. But he refused to countenance the primary‑purpose test’s motive parsing amid ongoing emergencies.

The forensic line of cases spawned from Crawford further demonstrates how Justice Thomas’s rule would operate. As we covered in the background, Thomas joined the majority in Melendez-Diaz to deem sworn analyst certificates testimonial. That result fits his approach because the certificates looked like formal substitutes for in‑court testimony. He also supplied the fifth vote in the fractured Williams v. Illinois case, but he did so based on a different rationale from Justice Alito’s plurality. For Thomas, revisiting that case’s facts, the outside lab’s DNA report was not testimonial because it lacked the formality and solemnity of an affidavit or deposition. He rejected the plurality’s “not for its truth” theory and remained focused, as before, on form, not on use or purpose. Again, that is the hallmark of his approach.

Justice Thomas’s pattern of Confrontation Clause analysis has continued in Smith v. Arizona. Returning to that case, Thomas joined the parts of the Court’s opinion that rejected the “not for its truth” label when an expert conveys an absent analyst’s factual assertions that matter only if true. But he wrote separately to reiterate that the controlling question on remand is whether the statements at issue have the requisite formality and solemnity to qualify as testimonial. If they do not, the Confrontation Clause “poses no barrier to their admission.” That is the same view he flagged in Bryant and Davis, now carried forward to a modern laboratory record.

Ultimately, then, Justice Thomas is a clear vote to jettison much of the post‑Crawford Confrontation Clause jurisprudence, starting with the primary‑purpose test. Instead, Thomas would push for a clear, formalist rule. The Sixth Amendment applies only to out‑of‑court statements that carry a specific degree of formality and solemnity, making them the functional equivalent of in‑court testimony. Emergency statements, child‑abuse disclosures to teachers, and other informal exchanges would generally fall outside the Clause because they lack the solemn, formal features that mark testimony, without the need to analyze competing purposes. Sworn or certified statements that look like trial substitutes would be squarely in. Laboratory materials would divide along the same formal line. A sworn certificate prepared for prosecution would implicate confrontation. A technical report that is not formalized in the relevant way would not, even if it later becomes probative at trial. My sense is that Justice Thomas sees that formalist clarity as a virtue. It is rule‑bound and historically focused, and it avoids what he views as speculative motive inquiries.

Justice Alito

Justice Alito is certainly the most direct and consistent critic of Crawford’s doctrinal framework. His answer to the core question is clear, as he would unreservedly jettison the testimonial‑plus‑primary‑purpose test.

In its place, Justice Alito would substitute a much narrower rule, one he has been developing for over a decade. Namely, Alito would confine the Confrontation Clause’s reach to statements that are either formalized (like an affidavit) or those that are created with the specific purpose of accusing a known, targeted individual. This approach would dramatically shrink the Clause’s footprint in modern criminal trials.

The best statement of Justice Alito’s alternative reconceptualization of the Confrontation Clause comes by way of his plurality opinion in Williams v. Illinois. As we touched on earlier, that case was badly fractured, but Alito’s opinion proposed that the Confrontation Clause attaches only when a statement is formalized in a way that resembles in‑court testimony, or when its primary aim is to accuse a particular person. Under this two‑pronged view, a non‑sworn lab profile created while police are still searching for an unknown assailant would sit entirely outside the Clause’s scope. Williams did not command a majority, but the template it offered, coupled with Justice Alito’s later writing, aptly describes the rule he clearly prefers.

His forensic opinions fit that template perfectly. In his dissents in Melendez-Diaz and Bullcoming, which we’ve established were the key forensic cases, he rejected the idea that every certifying analyst is a constitutional “witness.” His core objection was that treating neutral technical records, which may have been created long before a suspect was identified, as accusatory testimony stretches the Sixth Amendment beyond its proper historical bounds. The same instinct animated his separate opinion in Smith v. Arizona. In that recent case, he agreed with the Court’s judgment that a testifying expert cannot simply “parrot” an absent analyst’s conclusions. But he wrote separately, joined by the Chief Justice, to argue that courts should retain flexibility. He urged that experts be allowed to describe some of their underlying work with a limiting instruction that the basis material is not received for its truth. That proposal shifts significant weight back to Federal Rule of Evidence 703 and trial management. Moreover, as we began with, Justice Alito’s recent statement respecting the denial of certiorari in Franklin v. New York makes the current stakes explicit.

Thus, if votes were available, Justice Alito would lead an effort to replace the Davis and Bryant primary‑purpose test. Taken together, Justice Alito’s opinions and votes across the Confrontation Clause landscape evince a consistent vision for reform. For Justice Alito, the primary‑purpose test is a failure. He would replace it entirely, applying the Sixth Amendment only when a hearsay statement is a targeted accusation or a substitute for live, formal testimony. Ordinary evidence law should handle all else.

Justice Kagan

Justice Alito might want to raze Crawford’s doctrinal progeny, but Justice Kagan is ready to reinforce it. In fact, Justice Kagan’s approach to Crawford is the direct opposite of Justice Alito’s. She is the Crawford framework’s most vocal defender on the current Court. Justice Kagan would unequivocally keep the testimonial framework and continue to apply the primary‑purpose analysis. She treats Crawford and its progeny as a sound return to a basic trial right, and her opinions are focused on fortifying it against evidentiary “end‑runs” and procedural loopholes that would drain the confrontation right of its meaning.

Justice Kagan’s majority opinion in Smith v. Arizona is the current lodestar for this approach. The opinion states plainly that if a testifying expert relays the factual assertions of a non‑testifying analyst, and those assertions matter only if they are true, then the prosecution has put those assertions before the jury for their truth. The Confrontation Clause applies in full, and evidentiary rules like Rule 703 cannot be used as a workaround to change the Constitution’s meaning. It’s a clear pragmatic application of Crawford that stabilizes trial practice and blocks a common evasion. In many ways, that opinion effectively adopts the reasoning from her dissent in Williams v. Illinois. In that Williams dissent, she laid the groundwork for this, praising Crawford for replacing a malleable reliability screen with a simple process‑based rule that asserts, quite simply, that when the state relies on a person’s testimonial assertion, the defendant gets to confront that person.

But Justice Kagan’s acceptance of the primary‑purpose analysis is measured rather than wooden. She joined the Court’s opinion in Ohio v. Clark, which, as discussed in the background, concluded that a young child’s disclosures to teachers were non‑testimonial because the point of the conversation was to protect the child, not to build a prosecution. That vote reflects a pragmatic understanding that the primary‑purpose test is a useful, functional tool for separating informal statements in emergency or caregiving contexts from the formal, trial‑focused statements that the Clause targets.

Additionally, Justice Kagan’s anti‑workaround instinct is consistent across contexts. Looking back at Hemphill v. New York, she joined the near‑unanimous Court, which rejected New York’s “door‑opening” device precisely because of a sense that it smuggled reliability judgments back into the Confrontation Clause analysis. More recently, her dissent in the Samia v. United States redaction case shows how her method travels. There, she explained that redacting a co‑defendant’s confession to “the other person” can still leave the jury with the same accusatory message as naming the defendant, meaning the Confrontation Clause problem doesn’t just disappear. Once again, her dissent relies on the practical reality of how juries experience evidence.

For Justice Kagan, formalism’s promise of simple labels and limiting instructions fails to fulfill the Confrontation Clause’s guarantee that defendants can face their accusers in court. Instead, for Kagan, the Confrontation Clause demands functionalist application to sift out accusatory statements and provide the meaningful protection envisioned by the Sixth Amendment. My strong sense, therefore, is that Justice Kagan would affirm Crawford and its primary‑purpose test, seeing it as the correct and most functional way to apply the Clause.

Justice Sotomayor

Justice Sotomayor’s answer is firmly in line with Justice Kagan’s. She would keep the Crawford testimonial framework and continue to apply the primary‑purpose test. Her opinions, however, often show an even more distinct, context‑sensitive pragmatism, perhaps informed by her background as a trial judge and prosecutor. Her project is not just to affirm the Crawford framework, but to ensure that the primary‑purpose test is applied with a practical, realistic eye, separating genuine emergencies from structured, evidence‑gathering interrogations.

Her opinion for the Court in Michigan v. Bryant, which we covered in the background, serves as the touchstone for her approach (and, indeed, the primary‑purpose test itself). There, she treated a mortally wounded victim’s statements at a gas station as non‑testimonial. Her opinion carefully worked through the concrete features of the chaotic scene, arguing the exchange was aimed at resolving an ongoing threat, not at creating trial evidence. The opinion gives lower courts a realistic, functional way to handle emergencies without draining confrontation of its content in more formal settings.

Justice Sotomayor’s pragmatism of course has limits, especially when it comes to forensic proof. Her votes in the lab cases run in the other direction, as they should under a consistent application of Crawford. While she was not on the Court for Melendez-Diaz, she joined the majority in Bullcoming, which treated analyst certificates prepared for prosecution as testimonial and rejected surrogate testimony by a colleague who neither performed nor observed the test. She also joined Justice Kagan’s Williams dissent. The through‑line is that when the state relies on an analyst’s assertion to convict, that analyst is a “witness,” and the defendant gets confrontation.

Returning to Hemphill v. New York, her opinion for the 8‑1 Court (which she authored) made her commitment to the Crawford process unmistakable. She wrote that the trial judge’s sense that the jury needed reliable context could not justify admitting testimonial hearsay. More recent Confrontation Clause cases keep this picture reasonably clear. In the recent Smith case, she joined the majority to shut down the common expert‑basis workaround. And in Samia, she joined Justice Kagan’s dissent, which explained why redactions that obviously point to the defendant still function as accusations.

Taken together, Justice Sotomayor is a staunch supporter of the functionalism that typifies Crawford’s progeny. She seems inclined to use primary‑purpose analysis to preserve space for non‑testimonial statements in emergencies, but she will insist on robust confrontation in forensic and other structured contexts where the state uses a person’s assertion in place of live testimony.

Justice Gorsuch

My reading of Justice Gorsuch suggests he has a unique vision for the Confrontation Clause’s future. He seems fond of Crawford’s originalist turn, but also evinces a deep skepticism of the entire primary‑purpose framework, viewing the motive‑based tests from Davis and Bryant as an unmoored deviation from constitutional text and history. His project, then, is to roll the primary purpose framing back and, in its stead, fulfill and vindicate Crawford’s originalist revolution. That is, I think Justice Gorsuch would discard the primary‑purpose test and replace it with a simpler, and likely broader, “use‑at‑trial” rule based on text and history.

Justice Gorsuch has signaled this particular project for years. In the Franklin v. New York order we started with (a separate opinion from Alito’s repudiation of Crawford), Gorsuch openly questioned whether the primary‑purpose test “came about accidentally” and noted its lack of an originalist defense. Equally, his concurrence in Smith v. Arizona pointedly refused to join the parts of the majority opinion that relied on primary‑purpose analysis.

What would replace primary purpose? For Gorsuch, the question is simple. If the government seeks to use an out‑of‑court statement against a defendant as a substitute for live testimony, that person is a “witness against” the accused. At that point, confrontation is required unless a clear, founding‑era exception applies. This rule is functionally different from Justice Thomas’s, which rests on formality, and Justice Alito’s, which requires a targeted accusation. Gorsuch’s rule is triggered by the use at trial, not the statement’s creation motive.

Justice Gorsuch’s use‑at‑trial approach would have a significant practical bite, especially in forensics. Under a use‑at‑trial rule, it doesn’t matter whether a lab produced a profile before a suspect had a name. If the prosecution asks the jury to accept the analyst’s factual findings to convict, the analyst must appear. This is why he could agree with the bottom line in Smith without leaning on primary purpose. In his telling, useful fictions like “basis testimony” cannot erase the functional reality that the jury has been asked to accept a person’s statement as proof.

Thus, my strong sense is that Justice Gorsuch would overrule Davis and Bryant, not as a rejection of Crawford, but as the necessary completion of its originalist project.

Justice Barrett

Though her record on the Confrontation Clause is relatively thin, Justice Barrett appears willing to support Crawford and its progeny. Unlike Justices Kagan and Sotomayor, however, Justice Barrett’s support of the primary‑purpose test is likely to come from an originalist angle as she seeks to refine its edges with extensive historical analysis. Justice Barrett is not calling for an overhaul like Justice Alito, nor has she joined Justice Gorsuch’s originalist call to discard the primary‑purpose test entirely. Rather, my sense is she’s a stabilizer, committed to Crawford’s procedural core but focused on ensuring the doctrine is both workable and, above all, historically sound.

Justice Barrett’s recent votes show a solid commitment to Crawford’s baseline. She joined the 8‑1 Court in Hemphill v. New York, which refused to let a judge‑made “door opening” rule bypass confrontation. She also joined Justice Kagan’s full majority opinion in Smith v. Arizona, a decision that squarely shut down the common practice of using a surrogate expert to channel an absent analyst’s testimonial findings. Notably, she did not join Justice Alito’s separate concurrence in that case, aligning herself with the majority’s more robust view of the right. To my mind, these are not the votes of a justice looking to weaken the doctrine or open loopholes.

Justice Barrett’s separate opinion in Samia v. United States provides the best window into her method. In that Bruton‑adjacent joint‑trial confession case, she agreed with the judgment, but Barrett wrote separately (in an opinion that highlights a fascinating intra‑originalist methodological debate) to fault the majority for relying on late‑nineteenth‑century practices in its analysis. She argued that such evidence was too distant from the Founding to be controlling. Barrett’s methodological critique thus reveals her deep commitment to getting the Founding‑era history correct. That commitment shapes her entire approach to constitutional interpretation, but it has not led her to join broader calls to replace the primary‑purpose framework.

Taken together, Justice Barrett’s time on the Supreme Court hints at a preference for preserving Crawford and the primary‑purpose test, but bolstering it with a more historically grounded account of what “testimonial” means. She has noted that much of modern policing is directed at building cases and that courts need clear, historically grounded lines that separate formal accusations from the many other conversations investigations generate. I expect her to continue resisting judicial reliability exceptions. She appears to be a key vote to preserve the Crawford framework, including the primary‑purpose test, while focusing on refining that test’s boundaries to ensure they are historically sound.

Justice Kavanaugh

Justice Kavanaugh’s record is steady and, to my mind, quite clear. He’s a reliable vote to keep the Crawford framework, including its primary‑purpose test. He treats the doctrine as settled law and applies it without theoretical drama. He isn’t pushing for a Gorsuch‑style rewrite or an Alito‑style overhaul. His focus seems to be on maintaining doctrinal stability and ensuring the rules are administrable for trial courts.

His votes on the Supreme Court track this approach. He joined the broad majority in Hemphill to reject a judge‑made exception to confrontation. Perhaps most telling, he joined Justice Kagan’s full majority opinion in Smith v. Arizona. And tellingly, he did not join the Alito concurrence, which sought to preserve more room for admitting basis testimony with limiting instructions. That choice signals some level of comfort with Crawford’s current, robust application in the forensic space. His vote in Samia is likewise consistent, as he applied the Court’s existing Bruton framework for joint trials rather than using the case to rethink confrontation.

Contextually, this evidence fits Justice Kavanaugh’s broader jurisprudential methods. He seems to respect precedent unless it proves, in his view, wrong and unworkable, and he has given no indication he views Crawford that way. He seems to prefer incremental clarifications that help judges run trials, not conceptual rewrites. I therefore don’t see any sign he wants to replace the primary‑purpose test, as he seems comfortable with the status quo.

Justice Jackson

Justice Jackson’s position is reasonably clear, as it is grounded in both a pragmatic judicial method and her practical experience. As a former trial judge and public defender, Justice Jackson seems to approach Confrontation as a fundamental, hands‑on trial safeguard, not a mere formality. Jackson is therefore a firm proponent of the Crawford framework. My sense is she would keep the primary‑purpose test and vote to strengthen the doctrine’s application pragmatically by policing unrealistic workarounds that fail to protect the right in a real courtroom.

Her early votes led me to this conclusion. She joined Justice Kagan’s majority opinion in Smith v. Arizona, which barred surrogate experts from repeating an absent analyst’s testimonial statements for their truth. Her dissent in Samia v. United States, however, is her most telling writing on the subject. In that case, she joined Justice Kagan’s dissent and wrote separately to warn that the majority’s reliance on redactions and limiting instructions is “disconnected from trial reality.” She emphasized, from her practical experience, how juries actually experience evidence, arguing that a neutral placeholder like “the other person” still functions as a direct accusation when the surrounding context makes the target obvious.

This practical, anti‑evasion instinct places her squarely in the Crawford‑affirming wing of the Court, alongside Justices Kagan and Sotomayor. She accepts primary‑purpose analysis as a necessary functionalist tool to sort genuine emergencies from formal, evidence‑gathering accusations. But she strongly resists formalist labels, like “basis testimony” or “context,” when they are used to smuggle in an absent person’s assertion for its truth.

III. Nunn’s Take: Mapping the Votes and Predicting the Future

So, where does this leave us? I’ve traced the doctrine from Crawford’s revolutionary break with Roberts through the development and refinement of the primary purpose test. And, as Part II detailed, we have a Court with nine distinct, and often conflicting, views on where to go next. Justice Alito’s and Gorsuch’s statements in Franklin v. New York frame the question perfectly. Is the primary purpose test an unmoored judicial creation that has created a “morass,” and is the Court ready to “reconsider” the entire framework?

My descriptive analysis, based on the map of views we just covered, points to a clear prediction. Despite the sharp critiques from Justices Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch, the votes are simply not there to overrule the Davis and Bryant line of cases. The primary purpose test is secure, not because it has universal enthusiastic support, but for two key reasons. First, a stable majority of the Court believes it is, at minimum, a workable and necessary tool. Second, and just as important, the critics who would replace it are themselves deeply and irreconcilably divided on what the replacement should be.

The future of the Confrontation Clause, therefore, will not be a revolution. It will be a contest at the margins over fortification and refinement. The core Crawford framework is safe, and the real action is in the trenches, focused on policing the line between testimony and non‑testimony, especially in the crucial context of forensic evidence. Let’s break down my prediction.

The Roberts Reliability Era Is Not Coming Back

Before we get to the fault lines, let’s start with the bedrock. If “reconsidering Crawford” means returning to the Ohio v. Roberts regime of conceptualizing the Confrontation Clause as a proxy for simply assuring the trustworthiness of a statement, the answer is a resounding and unanimous “no.” There is zero appetite on the current Court for resurrecting the old standard, which allowed judges to admit testimonial hearsay, even in the absence of cross‑examination, if they found it bore “adequate indicia of reliability.”

This point is the one thing Justices Kagan and Alito, or Justices Thomas and Sotomayor, can all agree on. The Roberts test has been thoroughly discredited as atextual, ahistorical, and “permanently, unpredictable,” as Justice Thomas once put it. Even Justice Alito’s call to action in Franklin, which was a direct shot at Crawford’s progeny, did not suggest reviving reliability balancing. His critique is that the primary purpose test has become just as much of a “morass” as Roberts was, not that Roberts was correct.

The Court’s recent 8‑1 decision in Hemphill v. New York is, to my eye, the nail in that coffin. Recall again that there, in an opinion by Justice Sotomayor, the Court squarely rejected a state‑law evidentiary rule that allowed a judge to admit testimonial hearsay to “correct a misleading impression.” The Court held that the Confrontation Clause is a procedural guarantee, a right to cross‑examination, not just a flexible tool that trial judges can set aside when they believe the jury needs to hear “reliable” but unconfronted evidence.

Thus, the Crawford revolution’s central holding, that the Confrontation Clause guarantees a procedure (cross‑examination for testimonial statements) rather than a substantive outcome (the admission of reliable hearsay), is safe. That battle is over. The debate that remains is the one Crawford itself started. What does it mean for a statement to be “testimonial?”

A Clear Majority Wants to Keep and Refine the Primary Purpose Test

My strong sense is that Davis’s and Bryant’s primary purpose test will survive as the primary methodology for determining whether a statement is “testimonial” under Crawford. A stable majority of at least five, and perhaps six, justices supports its continued use. Notably, this bloc isn’t monolithic. It contains a pragmatic core focused on fortification, a set of institutional stabilizers, and an originalist refiner. But they all converge on the same bottom line, preserving the primary purpose framework as the baseline for operationalizing Crawford’s “testimonial” standard.

One group of supporters for the primary purpose test is a pragmatic core consisting of Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson. They are the framework’s most consistent defenders. For them, the primary purpose seems to be a necessary, functional tool to execute Crawford’s mandate. For example, Justice Sotomayor’s opinion in Michigan v. Bryant is the canonical defense of this approach, a deeply practical analysis of a chaotic scene to determine that the participants’ purpose was resolving an emergency, not creating a trial record.

This functionalist group’s modern project is fortification. In the more recent cases, they seem focused on shutting down the evidentiary end‑runs that prosecutors and courts have used to evade and bypass confrontation. Justice Kagan’s majority opinion in Smith v. Arizona is the perfect example on this front. As noted, it decisively closed the “basis testimony” loophole, making clear that an expert cannot be used as a conduit to parrot the testimonial findings of an absent analyst. Likewise, Justice Jackson’s practical dissents and concurrences, like her separate writing in Samia v. United States warning against judicial fictions that ignore “trial reality,” place her squarely in this camp. For these justices, the primary purpose test works, and the Court’s job is to ensure it is applied robustly and realistically.

This pragmatic core is joined by Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett. Their votes in Hemphill and, crucially, in Smith show they are likely on board with the Crawford project. They both joined Justice Kagan’s full majority opinion in Smith, significantly declining to join Justice Alito’s concurrence, which sought to preserve more room for admitting basis testimony with limiting instructions. To my mind, this move signals they are not looking to weaken the doctrine.

Their reasoning, however, adds a different texture. Justice Kavanaugh appears to be an institutional stabilizer, at least in this discrete context. He treats the Davis and Bryant primary purpose test as settled law and is focused on administrability and stability, not a theoretical rewrite. Justice Barrett, by contrast, seems to be more of an originalist refiner. Her vote in Smith confirms her commitment to the Crawford procedure, even as her separate writing in Samia shows her deep methodological focus on getting the Founding‑era history correct. Crucially, then, Justice Barrett is not a pragmatist in the Kagan/Sotomayor mold. Instead, she will likely support the primary purpose test by seeking to ground its application in a more thorough historical account of what “testimony” meant in 1791, refining its edges rather than replacing its core.

Finally, Chief Justice Roberts lands in this camp, albeit as its most hesitant and tentative member. In the Confrontation Clause context, like many others, the Chief seems to adopt the role of a managerial institutionalist. He joined the majority opinions in Davis and Bryant, so he accepts the primary purpose test as the governing standard. But his dissents in Melendez-Diaz and Bullcoming show his long‑standing discomfort with applying the Confrontation Clause’s full force to forensic evidence. Moreover, his decision to join Justice Alito’s concurrence in Smith seems to be a key tell. He agrees that an expert can’t just be a parrot (Smith’s core holding), but he still wants to keep the door open for admitting some expert basis evidence with a limiting instruction, relying on evidence rules like Federal Rule of Evidence 703 to manage the trial. Chief Justice Roberts thus creates the one point of real tension within the majority.

Nevertheless, my overarching prediction is that a reasonably solid bloc of five‑plus justices (Kagan, Sotomayor, Jackson, Barrett, Kavanaugh) will preserve the primary purpose test as the primary means of determining if a statement is “testimonial” under Crawford and, correspondingly, within the ambit of the Confrontation Clause’s protection.

Fractured Critiques Aiming to Jettison and Replace the Primary Purpose Test

Standing opposed to the bloc that continues to support the primary purpose test and Crawford’s current lineage are three vocal critics: Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch. They provide the doctrinal fireworks, and their critiques in cases like Franklin are what spark posts like this one.

Quite clearly, these three justices all agree that the primary purpose test is a judicial invention gone wrong. And they would all likely vote to jettison it tomorrow. But the unanimity of the dissent ends there. The current opposition to the primary purpose test has no real path to a majority, because they cannot even form a coalition of three. That is, their proposed alternatives to the primary purpose test are themselves fundamentally and irreconcilably at odds. In essence, then, the dissenters are not allies, but instead are three separate, competing revolutionaries.

As we saw in Part II, Justice Thomas offers the longest‑standing alternative, a bright‑line test based on “formality and solemnity.” His approach would discard the primary purpose test entirely. Instead, the Clause would apply only to statements that are the functional equivalent of in‑court testimony, like sworn affidavits (which explains his vote in Melendez-Diaz), while excluding informal statements at a crime scene (his view in Davis and Bryant).

Justice Alito’s proposal, as outlined in his Williams plurality, is different. He would replace the primary purpose test with a two‑pronged rule, applying the Clause only if a statement is either (1) formal, like an affidavit, or (2) made with the primary purpose of accusing a specific, targeted individual. This formulation is complex because it is simultaneously broader and narrower than Justice Thomas’s. It is broader because its second prong would cover informal but targeted accusations (like the statements in Hammon), which Justice Thomas’s formality‑only test would exclude. But in another, crucial respect, it is narrower. As his Williams reasoning shows, Justice Alito places immense weight on the “targeted accusation” prong, arguably treating it as a decisive filter. This focus explains why he’d find many lab reports non‑testimonial. If the analyst is just processing a sample without a specific suspect in mind, the statement isn’t a “targeted accusation” and thus, in his view, falls outside the Clause.

Finally, Justice Gorsuch rejects the primary purpose test as lacking originalist justification, but his replacement is starkly different from the other two dissenters. As detailed earlier, he proposes a “use‑at‑trial” rule. For him, the question isn’t the statement’s form (like Thomas) or its creation motive (like Alito and the majority). The simple question is whether the prosecution is using the out‑of‑court statement at trial as a substitute for live testimony. If so, the declarant is a “witness,” and the Clause applies. This test is arguably the broadest and would cover any forensic report offered for its truth, regardless of its formality or whether it was “targeted.”

Ultimately, then, these three alternatives cannot co‑exist, which is why I think this bloc of critics will fail to overturn the primary purpose test. Their theories conflict directly.

Justice Gorsuch’s “use‑at‑trial” test, for example, is far broader than Justice Thomas’s approach to the Confrontation Clause. Take a statement like the one in Hammon, where a victim tells police at the scene about a past domestic assault. For Justice Thomas, that statement would be non‑testimonial because it lacks the formality and solemnity of an affidavit or deposition. For Justice Gorsuch, however, the same statement would be testimonial if the prosecution uses it at trial to prove what happened, regardless of its informal character.

Justice Gorsuch’s test is also broader than Justice Alito’s approach. Consider a DNA profile created before police have identified a suspect, like the report in Williams. For Justice Alito, that report is non‑testimonial because it was not created to accuse a targeted individual. For Justice Gorsuch, the report becomes testimonial the moment the prosecution offers it at trial to prove a fact necessary for conviction. The creation motive is irrelevant, as the use at trial is what implicates the Confrontation Clause.

The conflict between Thomas and Alito presents a more complex overlap. It reveals a critical split on which formal statements count. Imagine a sworn, formal lab certificate created as part of routine testing before any suspect is identified. For Justice Thomas, the formality and solemnity of the sworn certificate make it testimonial, full stop. For Justice Alito, however, the same certificate would likely be non‑testimonial because, despite its formality, it was not prepared to accuse a specific, targeted person.

Ultimately, then, these three alternatives cannot fully reconcile, which is why I think this bloc of critics will fail to overturn the primary purpose test. Those currently opposing post‑Crawford doctrine have no unified alternative theory for deeming statements testimonial. To be sure, they all agree in their view that the primary purpose test is problematic, but they currently lack a common ground on what to build in its place.

My Prediction on the Fate of Crawford

If Crawford were reconsidered tomorrow, what would be the result? Here’s my prediction.

Part I of that opinion would be unanimous and anticlimactic. It would simply reaffirm that the Ohio v. Roberts regime is dead and buried. All nine justices would sign on. The old days of letting judges bypass confrontation based on their own “indicia of reliability” are gone for good. The Court is in total agreement on this point. Hemphill v. New York, for instance, serves as the tombstone for the Roberts era by cementing the rule that the Confrontation Clause guarantees cross‑examination, not a subjective judicial stamp of reliability.

Part II of the opinion is where the real debate would be. The majority opinion here would uphold the Davis and Bryant “primary purpose” test as the governing standard for sorting testimonial from non‑testimonial statements under Crawford. This holding would command a solid majority, likely six votes, even as the coalition is a fascinating mix. At its center, you have the pragmatic bloc, consisting of Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson, who view the test as a vital, functional tool. They’d secure their majority with Justice Kavanaugh, acting as an institutional ballast, and Justice Barrett, who appears committed to Crawford’s procedural core but, as an originalist, wants to refine the test’s historical grounding, not replace it. Finally, Chief Justice Roberts would almost certainly join this holding as well, though perhaps with a separate concurrence emphasizing his more tentative views.

By contrast, Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch would almost certainly dissent from the Part II holding, arguing that the primary purpose test is an unworkable, judge‑made creation lacking historical support. But as we’ve discussed, the critics are fundamentally divided. We’d therefore likely see three different dissenting opinions proposing three different alternatives to the primary purpose test. But because this dissenting faction cannot coalesce around a single alternative, they have no real path to a majority.

Thus, my prediction is clear. Crawford and the primary purpose test are here to stay.

Password Change Information

Your account uses a social login provider. To change your password, please visit your provider's website.